Putin Grooms a New Generation of Leaders

The Russian president is removing old allies and replacing them with young loyalists, likely ensuring his leadership will continue until 2024.

After 16 years in charge, Vladimir Putin is shaking up his team to cement his control into the next decade. The 63-year-old leader is pushing aside some longtime allies and grooming young lieutenants—many of whom share his background in the security services and aren’t old enough to have worked under any other leader—to form a new generation of Kremlin leadership. One of them could even become his successor one day.

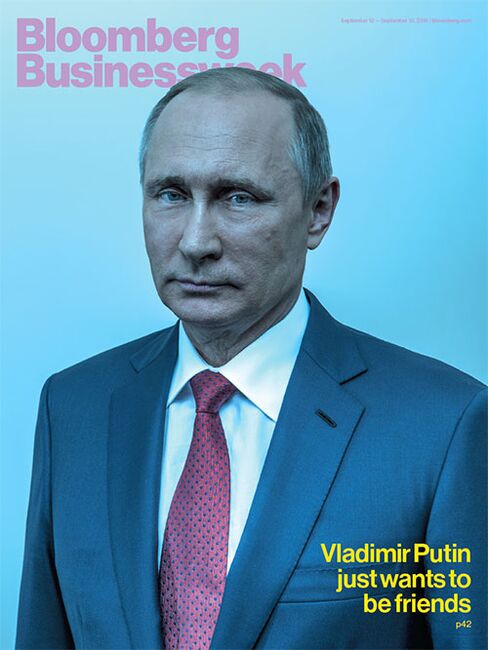

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek, Sept. 12-18, 2016. Subscribe now.

Photographer: Jeremy Liebman for Bloomberg Businessweek

In his interview with Bloomberg, Putin wouldn’t admit he’s planning to run for another six-year term in 2018 (almost everyone in Moscow’s political establishment believes he will), but he made clear he’s settling in for the long haul. He’s already ordered top advisers to come up with a program for his next term. Key attributes for a potential successor when the time comes? “A

young person” but a “mature person,” was as far as he would go.

After two years of plunging oil prices and economic pain that have barely dented his popularity rating of more than 80 percent, Putin sees stability, not stagnation. He sharply rejects the idea that his bold moves outside Russia—like the military foray in Syria and the annexation of Crimea—are at odds with his reluctance to make the changes at home that even his advisers say are needed to get the economy back on track. “On the whole, we’re moving in the right direction,” he says.

young person” but a “mature person,” was as far as he would go.

After two years of plunging oil prices and economic pain that have barely dented his popularity rating of more than 80 percent, Putin sees stability, not stagnation. He sharply rejects the idea that his bold moves outside Russia—like the military foray in Syria and the annexation of Crimea—are at odds with his reluctance to make the changes at home that even his advisers say are needed to get the economy back on track. “On the whole, we’re moving in the right direction,” he says.

The next decade will be harder in many ways than Putin’s first, when surging oil prices helped him almost double the size of the economy, drive up living standards, and centralize Kremlin control. Even before Western sanctions and falling crude prices knocked Russia into recession last year, growth had begun to stall.

Now the pressure to stretch every kopeck has become intense. Putin, long known for standing by his closest allies, has begun pushing some old-timers out. First to go was Vladimir Yakunin, 68, in August 2015. As head of the national railways, the country’s largest employer, he’d become known for his repeated appeals for more government aid. The removals picked up this year, with longtime aide Viktor Ivanov, 66, removed in the spring as head of the antidrug police. Sergei Ivanov (no relation), a 63-year-old whose ties to Putin go back decades to the Soviet KGB, was dropped as Kremlin chief of staff in August.

“There’s almost no one left from the original politburo,” says Olga Kryshtanovskaya, a specialist on the Kremlin elite at the Russian Academy of Sciences. “The demands for efficiency are now higher. The survival of the system is at stake,” says Alexei Makarkin, deputy head of the Center for Political Technologies, a Moscow political consultancy. Putin’s “goal is to preserve his rule for the long term, relying on new people and new blood,” he says.

He’s been elevating younger officials, many who began their careers when he was already president. The new Kremlin chief of staff, Anton Vaino, 44, started out as a low-level protocol official in 2002. Some ex-bodyguards have been installed as regional governors to give them a chance to build political experience.

One, Alexei Dyumin, 44, spent years at the president’s side ready to take a bullet to save him. Now, some aides say Putin and Dyumin have a special bond, that the president sees him as among the most trusted and loyal, putting him on the political fast track soon after he served a few months as deputy defense minister. Asked about the promotions of Dyumin and other security service veterans, Putin says, “The most important thing is that the right person wants to grow, is capable of growing, and wants to serve the country. If he wants it, and I can see that the person has potential, then why not let him work?”

Putin isn’t purging his entire inner circle just yet, of course. Several longtime allies remain in top jobs, and at least one was recently promoted. Putin has nothing but praise for Alexei Miller, 54, who as head of state gas giant Gazprom has presided over an 80 percent drop in its market value. “This absolutely doesn’t worry or bother us,” Putin says of the market plunge. “We know what Gazprom is, what it’s worth, and what it will be worth in the coming years.” Putin put Miller, an associate from the 1990s in St. Petersburg, in as chief executive officer in 2001.

Photographer: Jeremy Liebman for Bloomberg Businessweek

The new generation is steeped in the state-controlled system that Putin has built. While some of his contemporaries might have had the stature to challenge the president in private, the younger officials owe their entire careers to him. That bodes ill for the overhauls that could jump-start the economy—loosening state control, stimulating private business, and cutting wasteful government spending. Putin has long resisted such steps in practice, despite embracing them in public statements.

Putin points to signs the worst of the recession is over. He also hints that state oil major Rosneft might be allowed to bid for a smaller rival in a planned privatization auction, something pro-market officials argue would only reinforce government control.

Read more bloomberg.com

Comments

Post a Comment